What you pawn, I will redeem

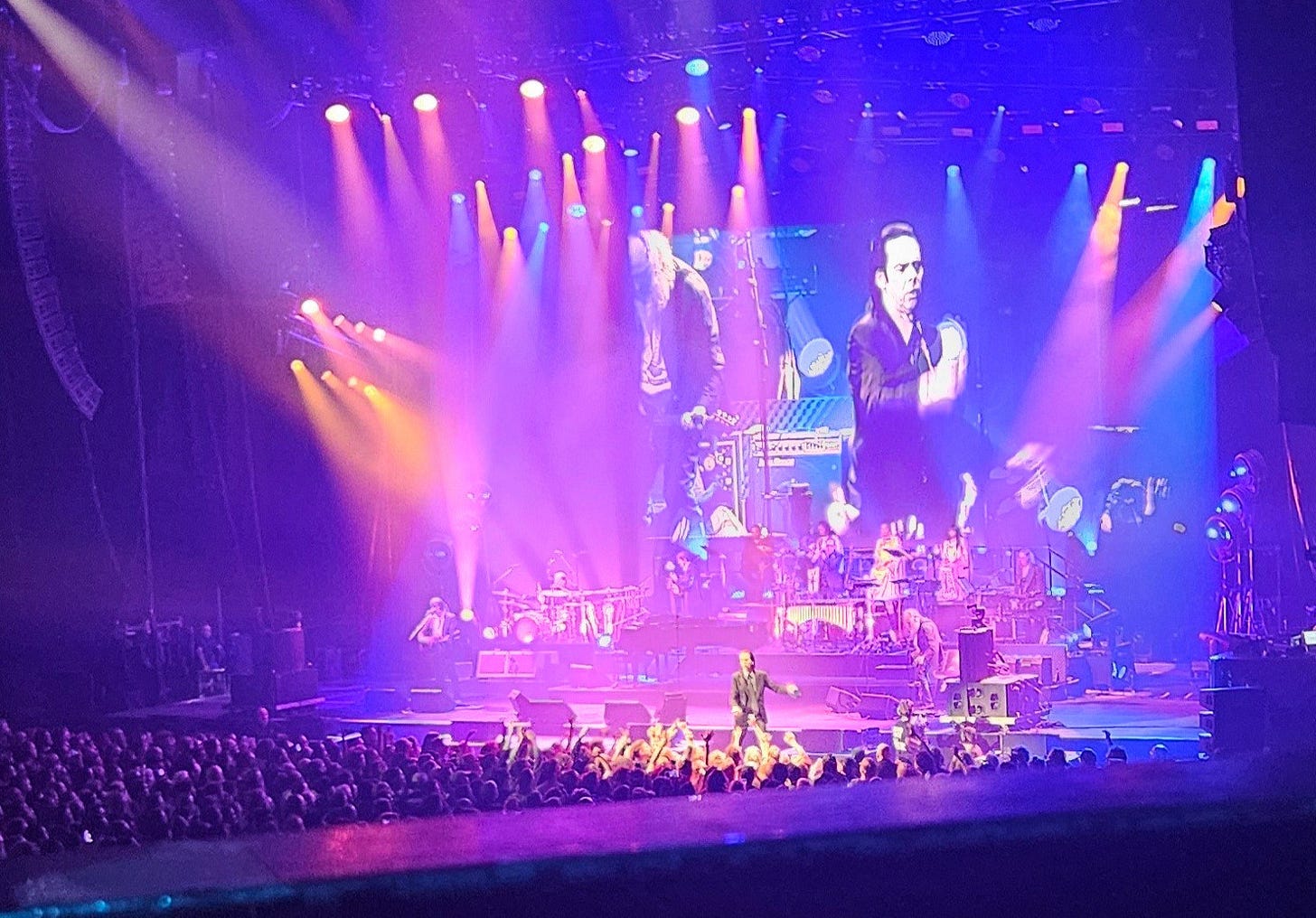

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds at the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, May 14, 2025

It’s Eurovision Song Contest week in Europe and here, too, if you like that sort of thing: that is, watching performers from every country in Europe (plus Australia and Israel) pitted against one another in a wacky display of kitsch. In an idle moment the other day, I watched the semi-finals just before I went to see Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds at the Bill Graham Civic Center, and it begged this question: What makes Eurovision’s music so cheesy in comparison to Nick Cave’s? For if you were from, say, Mars, you might have a hard time distinguishing between – say -- Croatian entrant Marko Bosnjak singing ”Poison Cake” and Nick Cave singing, oh, “From Her To Eternity” or “Red Right Hand.”

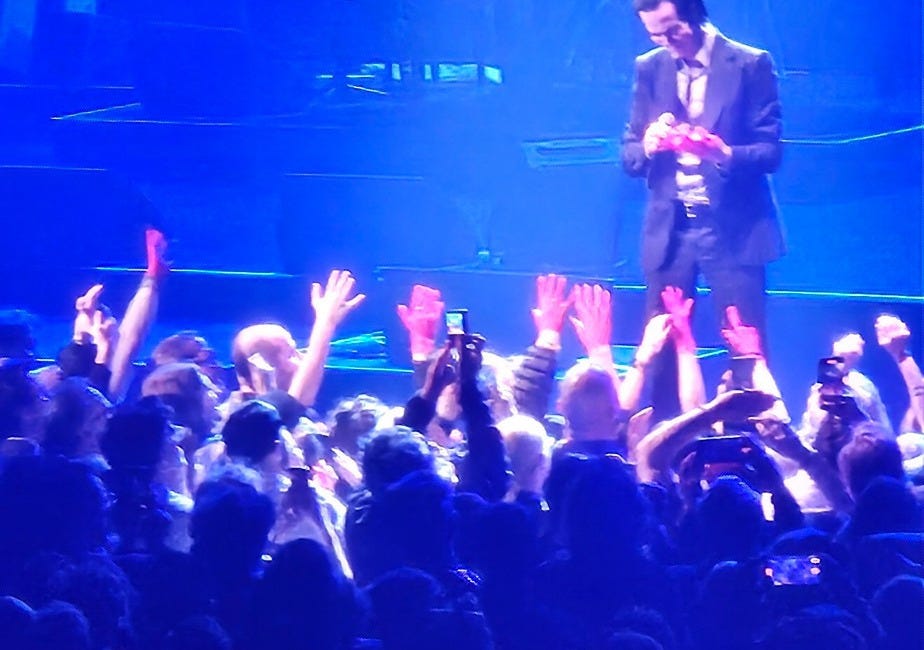

Both performances feature death, drama, theatrics and an artistic persona, as well as a crazed audience of devotees frantically waving stuff in front of the stage. But one song is goofy and the others are…not.

Is it Nick’s anguished back story that makes him have so much gravitas? Is it the depth of his performance, or his band? I can’t figure it out, but I can assure you that a night spent with Nick Cave is worth the bother, especially in times like these.

I was on the fence about going to see Nick Cave, mostly because of the venue. I hadn’t been there in a long time, but I knew it was one of those places you always leave thinking, “never again!” If memory served, the Bill Graham Civic Center is a barn, and anyway, at the time tickets went on sale I couldn’t be bothered to get in the phone queue.

But that was then and this is now, and since then – the Fall – the world has fallen apart. Nick Cave’s oeuvre suits bad moods and dark zeitgeists, and when the time came it felt worth the hundred bucks it cost to sit in an excellent seat in the front row of the balcony. I grew up in a non-religious – almost anti-religious – household, but I too struggle sometimes with thoughts about good vs. evil, the meaning of life, and why bad things are allowed to happen by a non-interventionist God. Indeed, the older I get, the more mortality is on my mind, and since mortality and the human condition is Nick’s stock in trade, a visit to one of his shows was well in order.

The last time I saw him with the Bad Seeds was in 2017, at the very start of the current catastrophe. In the review I wrote then, I quoted Dwight Garner, saying, “It is impossible to read anything in 2017, or to write anything, without thinking of America’s political and moral landscape. It is tendentious to mention it in every review, but I am thinking of it while writing every review,” and that is how I felt, both then and now.

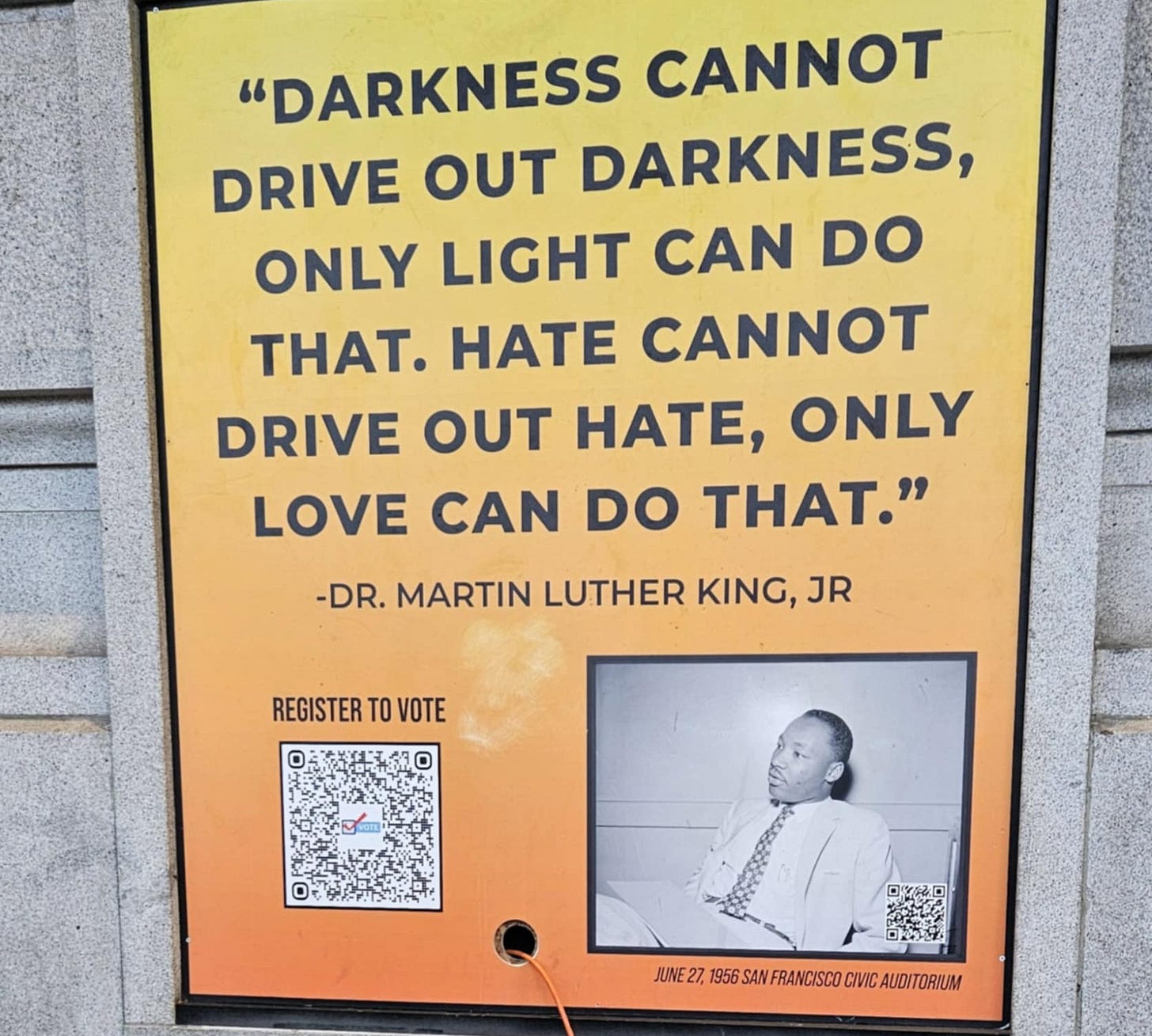

But then, was a little different. Then, the feelings I personally remember experiencing were mostly outrage. Now it is decidedly fear, grief and anxiety, and either way, Nick speaks to those emotions directly. A Eurovision song contestant may have some message to give us about life, or love, or cancer. And other, more credible artists, can deliver us powerful messages about politics, or justice or art. But as a man who has lost not one but two of his children, Nick Cave’s messages go well beyond that, into a realm that few dare to speak about…indeed, his metier is the unspeakable.

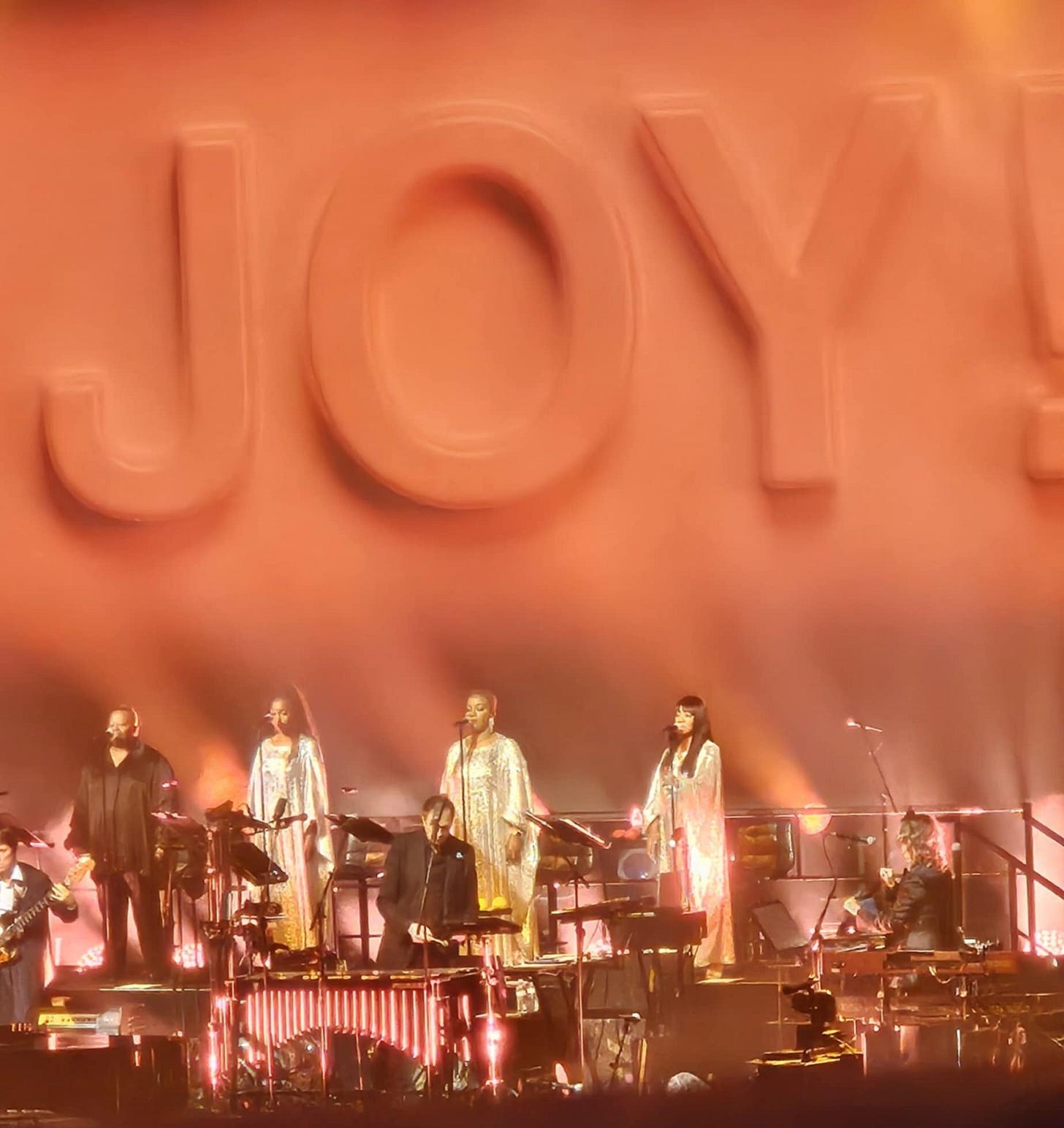

Because of his experiences, he is to be believed when he tells us that a long dark night is coming down. He is to be believed when he describes these times as rape and pillage in the retirement village. When he says that everyone is hidden, and everyone is cruel, and that there’s no shortage of tyrants and no shortage of fools. Believe him when he tells us that this is the weeping time, but most of all, believe him when he tells us that however bad the world is, the stars are still a bright triumphant metaphor for love. When he sings, “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy.”

The Bill Graham Civic is still a barn though, and so jenky that when one man in my row sat down, he broke the seat off its hinge. From where I sat, I had a fantastic view of the proceedings but in the end, I had to go downstairs and mingle after all: it was too alienating up there, and I was glad I did: from the back of the house, the proceedings can seem a trifle somber, but in the midst of the fandom, a Nick Cave crowd is almost hallucinatory. At its best, in that space, the notes that are played and the words that he speaks and the rhythm, and the chorus, and the violin meld into a solid object, and it fills a room visibly, like a shape or something: you can almost touch it as it wafts around the arena. And in those moments, it doesn’t even matter if you’re at a barn like the Civic, redemption will still be on offer.

This was Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds last US performance – or rather, last but one, as they are appearing this weekend at the Cruel World Festival in Pasadena this weekend, but as he himself said, “that’s not a ‘real’ show…” a statement I’d love to unpack sometime. Anyway, they’re on their way out of here for a while, and the show I saw actually had that end-of-tour feel of slight exhaustion hanging around it…unless the exhaustion was mine, and I was projecting.

But no matter. The truth is that, Ol’ Nick is a victim of his success. If 8,500 people want to see him then I guess he has to play these kinds of venues, but his particular artistry works better in a more intimate setting. And it made me wonder. Do those mega churches in SoCal and Texas seat 8,000? Because Nick is a preacher and his audience is a congregation, and watching him made me think about the showmanship involved in organized religion, and its relationship to technologies of sound, art, architecture. Wouldn’t Nick Cave’s shows be more fantastic if you could see and hear them in a cathedral? And wouldn’t those preachers in the megachurches benefit immeasurably if they gave the front rows red gloves for their right hands and had them raise them up every time they said the word ‘the devil’?

That there is a relationship between music and religion shouldn’t be surprising but what is surprising is the concomitant idea that the devil has something to do with it. You know, like in the movie “Sinners,” where music both heals and damns the listeners, but that somehow, just by being present in its midst, we are able to refute this thesis. That’s what we go see Nick Cave for, after all. Not for the sturm and drang of the middle of the moment, but for the light that dawns at the end of it.