The agent of the spectacle placed on a stage is the opposite of the individual; the enemy of the individual in himself as well as others.

-- Guy Debord, Society and the Spectacle, paragraph 61

Once upon a time, many years ago, I was going to see a sold-out Chris Isaak show at a small club called the I Beam, and I saw a guy outside the club give the doorman $80 to get himself and his date inside. And I was outraged, because I didn’t think this guy even liked Chris Isaak: I could see he was just paying that amount of money to show off to his date. But looking back, I see how naïve I was, because of course that’s what he was doing: in the world of dating, that is practically mandatory behavior.

I was dumb and naïve not to have known that, but I was mad because I desperately wanted the audience to be full of people who genuinely loved Chris Isaak, and it was patently obvious to me that he didn’t. That concert happened at a time when culture was shifting such that some sub-cultural acts like Isaak were beginning to go mainstream, and for many years after, I often felt like one result was that people in the audiences were kind of disengaged from what was going on stage. But this is much less of a problem today. Nowadays, many concerts cost a lot more than $80, and although on the one hand that kind of sucks, it also guarantees that almost everyone in the audience is a psychotic fan of the act on stage.

That was the case with Taylor Swift’s “Eras” tour, a fact which I experienced up close and personal when she performed at Levi’s Stadium in July. Several weeks later, Beyoncé, whose music I much prefer and an act whose fans are, if such a thing is humanly possible, almost more psychically engaged than Taylor’s, brought her tour to the same venue, but even if I could have afforded it, I just didn’t have the mental energy to do it all over again.

Luckily for me, Beyoncé has put out a movie, Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé, which I was able to go see instead. So did Taylor Swift, but the Eras film is more like an old-fashioned concert film – like Stop Making Sense, Ladies and Gentlemen, The Rolling Stones or The Song Remains the Same, - while Renaissance AFBB, goes much farther, aesthetically. Both of them, however, are useful and lucrative texts in that they allow fans who couldn’t otherwise afford it to see the show live. And they probably also help to offset the truly enormous costs of mounting this kind of extravaganza.

In this context, it’s instructive to remember that Woodstock, the festival, originally lost money before the massively successful (and Oscar-award winning) film and record of the film came out a full year later. And in fact, some shots early in Renaissance AFFB reminded me a lot of early shots in Woodstock, like when they’re building the stage in the field in Saugerties. In it, hirsute young white men lift girders and hoist steel beams while an overhead shot pans across the pristine meadowland the concert will occur on later and a gorgeous couple of hippies crosses the screen on horseback, recalling to mind pioneers. Indeed, the whole thing looks like they are raising a barn, possibly to put a church in.

Renaissance contains a scene just like that one, only this festival is in a stadium in a city and the stage is being built by women. And this time, what’s being built actually IS a church, not only because her audience is worshiping there, but because what Beyoncé does in the venue is preach. She calls what she is doing with the stadium she is performing in “creating a safe space,” but I’d call it a T.A.Z. – a Temporary Autonomous Zone, that is, a temporary space which eludes formal structures of control: “The sixties-style “tribal gathering,” the forest conclave of eco-saboteurs, the idyllic Beltane of the neo-pagans, anarchist conferences, gay faery circles...Harlem rent parties of the twenties, nightclubs, banquets, old-time libertarian picnics…” These, according to its author Hakim Bey, are “liberated zones” of a sort, and despite their forbidding (and super-capitalist) price tag, I’d argue that so too are the hours spent during many such stadium concerts. In their confines, a ‘new territory of the moment’ is created, a pirate utopia where coffers are raided in aid of something other than the state, by someone other than the state.

This is just as true of the stadiums Taylor Swift fills as well, of course, but creating a safe space for black and queer people to elude formal structures of control is harder, more important, and more radical, and that is Beyoncé’s stated intention here. According to Okechukwu Nzelu, writing in Granta, Renaissance is “an engagement with the black queer community that draws deeply on its expansive culture and engages more directly than ever before with black queer people, those who are with us today and those who are not.” The LP, and the tour, feature artists like TS Madison, Big Freedia, Moi Renee and Kevin Aviance, as well as other stars and of the ballroom and voguing subculture, which Beyoncé says she deeply relates to thanks in part to a relative of hers who introduced her to that music and culture. By inviting all these performers onto the Renaissance tour with her, Beyoncé does for black queer culture what she did for HBCUs in Homecoming, and while that choice seemed both striking and correct for a concert taking place at Coachella, a venue filled with white college kids, this one seems somehow more joyous and genuine.

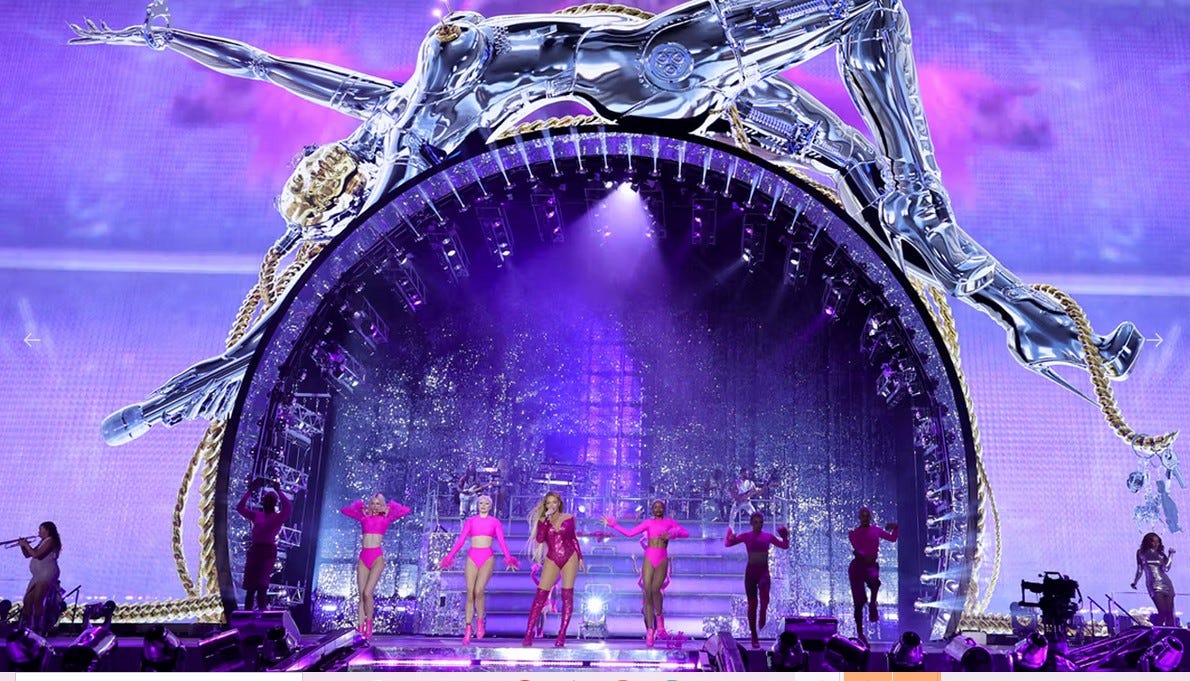

Renaissance AFFB does a fantastic job of both capturing that sense of spiritual bliss that people feel when ensconced in this world, both through shots of the crowd and of Beyoncé’s performance, and it also contextualizes the concert by showing it as a business undertaking which is frankly fascinating. I am still kind of stunned by the amounts of money this tour, as well as Taylor Swift’s, represent in the global economy, and the logistics of it all are absolutely astonishing. Just as one example, as we watch the stage go up, Beyoncé tells us in a voice over that her tour requires 160 trucks and that there are three sets of them on the road at any time, setting up the stadiums in advance. 160 trucks and three sets? The scale of this enterprise is almost unimaginable, and it is on display throughout the movie. Besides the many dancers and crazy, flashing costume changes, the vast video screens and new stadium roofs and all the extra stages, there is an enormous flying horse and a gold-plated army tank.

And yet…is any of this really new? When Beyoncé, astride an enormous reflective silver horse, was swung up, out and over the arena floor, I couldn’t help but think of the time I saw Motley Crue’s Tommy Lee sitting buck naked astride a drum set that was also flew over the Oakland Arena, there to rotate, end over end, while he tapped out the beat to a recording of “Kasmir.”

I read somewhere that this drum set and the apparatus involved were sitting in a warehouse, perhaps alongside Peter Gabriel’s giant hamster wheel, Iron Maiden’s sarcophagus, U2’s lemon-shaped space ship, and Spinal Tap’s Stonehenge. Soon the silver horse (or, all three silver horses) will join them there, and then, a thousand years from now, they will all be unearthed by scientists who will ponder what they were used for.

Doubtless those archeologists will conclude these things were used for religious rites, and they will be correct. In a way, thinking about such concerts that way really highlights the difference between seeing Beyoncé’s show in person and watching this film. I remember during the Pandemic that people who were religious really disliked going to Church over Zoom – in fact, in California many churches went to court over Covid restrictions that banned indoor services, and won. Seeing Beyoncé on film rather than in person may also represent a diminished emotional and spiritual experience, but Renaissance: A Film By Beyoncé is a fun and absorbing movie nonetheless; I can honestly recommend it for fans and non fans alike.