A few weeks ago I went to the movies and was dismayed to see not one but two people with dogs on their laps. I thought that was asking for trouble, but it wasn't nearly as concerning as the sight of an older man wearing a harmonica holder around his neck at the showing of "A Complete Unknown" which I attended on Christmas Day. I clutched my sister's arm.

"What if he...plays it?"

Happily, he did not: it was cosplay, like how little girls dress up as Moana or Barbie, big girls wear Taylor Swift sequins to showings of "Eras", and teenagers sometimes dress in suits and dance like minions at screenings of Despicable Me. In retrospect, I honor that guy's spirit. It exhibits all the kooky excitement kids can bring to the movies these days and that's perfect for a movie about Dylan, whose work always brought out the most keenly devoted and demented; indeed, he practically invented the idea of the fanboy, although they are generally given the more polite title of “Dylanologist.”

I liked "A Complete Unknown" a lot: it is a good movie even if you don't care about, or know, or even like the music of Bob Dylan. It only covers four years in his career -1961 to 1965, during which so much happened, and if four years sounds short (given that he's now been around for 63 more years) consider that Nirvana's entire career was from 1991 to 1995, and followed a similar trajectory, if not a similar end. Among its other virtues, this movie is therefore a great depiction of the arc of fame in 20th century America as it is lived by superstars. And it showcases how people like Dylan don't just step into fame by luck. They are, in fact, extraordinary people with a massively unusual take on the world that they are unafraid to spread. Dylan reminds me of Lord Byron and Oscar Wilde, two other men who stamped their vision on their eras in ways that still reverberate. ("Byronic" is an adjective we use to describe dark, sexy, handsome men who are absolute trouble, and Wilde's speech patterns and sarcastic wit are still adopted by some people as shorthand for 'flaming queer'.)

So all hail the screenwriters, James Mangold and Jay Cocks, for introducing us to the complex thinking behind rockism and poptimism that has fueled arguments about authenticity in music from then until now, and all hail the actors, especially Timothee Chalomet and Edward Norton, for doing an amazing job embodying these real people. I think Caryn Rose's review says it best, here - I don't want to repeat her points, so I won't. Everything she says is what I think too.

Caryn is especially right about most biopics getting everything wrong; to me what's most right about this one is embodied in the way it foregrounds the music. It shows how music itself gets made, both in studios and in the imagination, and it shows how people receive it, in a number of extraordinary scenes at folk clubs, concert halls, the Monterey Pop Festival, and finally, twice, at the Newport Folk Festival. The first scene showing the time when Dylan introduces the song 'The Times They Are a Changin’" is an absolute triumph in conveying the power of live performance, the ecstasy of it, and the way that particular artists can suddenly embody the zeitgeist in a way that actually changes it. I have lived through such moments; I recognize them for what they are when they happen, and this version of it is spot on.

(It made me a little sad though. In 1964, the times they were a changin’ as the arc of the moral universe bent toward justice. Today that arc irretrievably mangled, it is no longer an arc, it’s a boomerang.)

As for the performance a year later where Dylan goes electric: that phrase, and the whole event, is such a great metaphor for the anxiety of influence, or as I put in my dissertation, the way that power appropriates power (and, in Dylan’s case, power chords.) I posited then that maybe Dylan’s going electric could be read as a visible seizure of power, while the distortion that the amplifiers inflicted on his music – later cited by Pete Seeger and others as the source of their antagonism – only served to magnify the danger, and perhaps the audacity, of his move. Electricity is distortion made real, after all: they feared the distortion of their - and his - ideas.

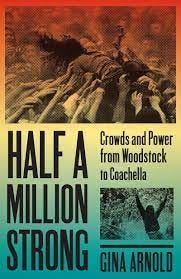

Later, I wrote a chapter in my book on crowds & power about this performance, which I treated more as an allegory rather than as a real event: truthfully, I didn't think very hard about the arguments that must have underpinned the actual performance (all of which are laid out here, and which are researched and discussed in Elijah Wald's book, 'Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night That Split the Sixties' which this movie credits as its source material). No one just gets on stage and "goes electric": you'd have to have all the instruments, amps and musicians in place, so I think my version is pretty thin comparatively. But here's what I wrote:

“Theodore Roszak notes, by 1966, ‘the neat distinction between dissenting activism and bohemianism are growing progressively less clear.’ So perhaps this lack of clarity was exactly what was so scary about Dylan’s later concerts: the sense that was once a community had become a crowd. Indeed, this inevitable transition from community to crowd is one that has always bothered rock fans and even rock artists: one if reminded of Kurt Cobain, who upon attaining wide-spread popular with a fanbase whose members didn’t reflect his own socioeconomic and political status, felt aggrieved that his records were in the same collections by bands he hated. As Cobain well know, by this time – the early 90 --, rock concerts had long become a kind of cultural shorthand for attendees, the fastest and easiest way to (temporarily) join in a certain shared consciousness. His fear was that the consciousness was a false one, and he was far from wrong.

In any event, the Newport Folk Festival of 1965 was the place where the spell was laid. The significance of Dylan’s performance there is not that it showed the world the importance of Dylan, but that it showed the world the importance of rock gatherings. No longer would the fields where rock ‘n’ roll drew its myriad fans together seem like silly pop dance parties for teenyboppers. Newport demonstrated that rock gatherings could and would be places where other meanings, other metaphors, and other messages could be acted out and then widely circulated. It heralded the approach of something somewhat terrifying: the shadow of an enormous crowd facing a far-off stage and listening together. Very, very, intently.”

(Excerpted from my book, Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella.)

I do think the movie upholds that concept, which is kind of gratifying. But finally, the movie made me think about the way that Dylan's whole career is really what created mine. Prior to Dylan, there wasn't really such a thing as rock critic as we know it: they came into being after him, as mostly white, mostly Ivy League-type young men began writing lengthy, flowery, screeds about the importance of this kind of music. Because of who they were, and because of who they revered, rock criticism evolved in a certain way, with the most credence given to certain types of artists (The Velvet Underground, for instance), while others were often ignored or criticized.

In this movie we briefly see Dylan extol Little Richard, Johnny Cash, and the Kinks, and we hear him-- and Pete Seeger -- diss “girl groups” and Patti Page. Ironically, just as Alan Lomax and others were angry about rock 'n' roll creeping into folk music, many rock critics have long been angry, or at the very least, disdainful, about other people's musical obsessions creeping into the canon.* Everything had to be in their own image. There’s a line in the movie where Dylan says, “people ask me where the songs come from, but what they really want to know is why they didn’t come to them.” That idea really underpins how I think many writers feel about the music they love. They wish they’d written it themselves.

I've thought this about the field of rock criticism, and resented it, for many years, but this movie at least made legible to me how that equation happened, and why it happened, and it lessened the feeling of being cursorily dismissed as a writer that I have naturally felt ever since. It reminded me of how, in that era, women's contributions not only to music, but to social life in general, were diminished and belittled, that is just how it was. This is what makes Joan Baez place in this world, and in “A Complete Unknown,” so astonishing, and for more on that, I can't wait for you to read my friend Addie Mahmassani's book Folk Woman, which comes out in September.

Anyway, you don't need to know any of this to enjoy "A Complete Unknown," because it’s just a good movie, period. To my mind, movies that depict pivotal true stories are only really great if they have a subtext which highlights some larger issue and event - and the more important it is, the better. This movie may pitch itself as a Dylan biopic, but it’s really more of a reverie on the increasingly positive and activist mood of America in the early 1960s. In other words, it is much needed.

*I think we saw an example of this weekend, when Beyonce got dissed - again - for something about her performance at some football game or other, though I didn’t pay attention because it was too dumb.

why does everyone obsess about some small mistake, desperate to point it out?

the points here are potent.

quibbling makes the quibbler seem impotent and unable to not succumb to the very thing Gina is calling out: diminish a woman's good work/thinking/analysis/creativity.

sadly.

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/dylan-destroyed-one-world-started?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios