Everything's Gonna Be Alright

It'll all be fine: the Opening Ceremonies of the 33rd Olympiad in Paris.

I’ve only been to two Olympics in person: the Athens ones in 2004 and the London Paralympics in 2012, and they were both absolutely fantastic experiences, highlights in my life of watching spectacles unfold. I sure wish I could be in Paris this week for the 33rd Olympiad, but because I can’t, I went to a giant bland Cineplex next to a Target in Sunnyvale California at 10:30 in the morning on Friday and watched the opening ceremonies on an IMAX screen.

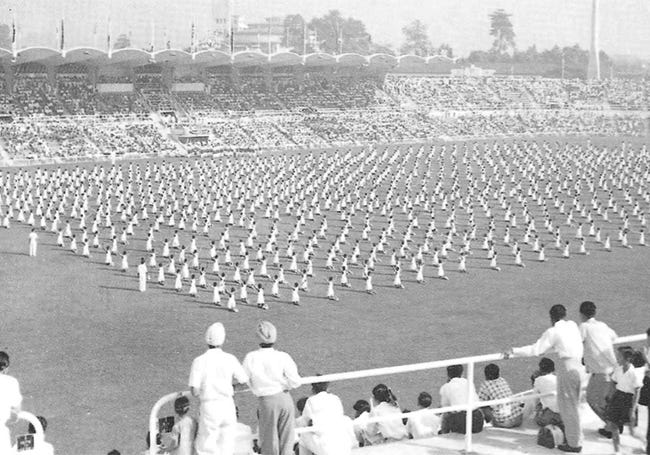

It was a far, far cry from being in Paris, I can assure you – architecturally speaking, perhaps the actual farthest point in the universe. But all the more reason to do it. You’re either in Paris, or you’re not, and the IMAX experience almost replaced being there. Anyway, it gave me a lot of food for thought, beginning with this one: once upon a time, when my eldest cousin’s wife Gillian was a little girl growing up in Kuala Lumpur, she told me she participated in a giant pageant to celebrate Malayan Independence. She was one of hundreds of little girls who knelt on their hands and knees in a formation in the center of Merdeka Stadium so that the design on the backs of their party frocks displayed the Malayan flag.

I couldn’t help but think of Gillian’s contribution to international pageantry during the opening ceremonies of the 33rd Olympiad in Paris, because the contrast between that low-tech gesture and what happened in Paris was just so enormous. Honestly, it is hard to believe they happened in one person’s – Gillian’s -- lifetime.

The Paris ceremonies didn’t even take place in a stadium; rather, they played out across the whole of Paris, on its rooftops and in its river. At one point, dancers hung from the scaffolding of Notre Dame Cathedral; at another, laser lights emanating from the Eiffel tower split the sky. There was a person who parkoured across a stretch of the city’s rooftops whilst holding the torch, and a weird sequence inside the Louvre which made it seem like the paintings had jumped out of their frames and into the river Seine.

Indeed, the theatrics of the Paris ceremony were on a scale so grand that they defied the space/time continuum. Only the pouring rain, which created visible drips on the cameras that NBC was using, allowed viewers like me to believe that what was going on was even real.

I think that it WAS real, though, at least most of it, but it was so totally over the top, and some of it was so, so, aesthetically bonkers, that when I accidentally walked into a theater showing Deadpool and Wolverine after going to the bathroom, it took me a little while to discern that a scene I saw of the two superheroes battling a CGI monster wasn’t just part of the schtick.

---------

The thing is, you either like this type of thing, or you don’t. I am a person who normally probably wouldn’t tolerate any of it, except for this kind of glitch in my personal history where I got all caught up in trying to make the Olympics. Indeed, I think watching the Olympics is almost the first thing I can remember watching on a TV (we didn’t own one, my parents had rented it for the occasion). What I watched that night was the diving, and here I am now, fifty years later, still practicing away, at diving, just getting worse and worse, but still frankly enjoying the heck out of it. I literally just finished practice before I wrote this.

Watching those first Olympics voided any sense of criticism I might otherwise have had about the games, is what I’m saying, despite there being so very much to criticize. And of course, my scholarly work is on society and the spectacle, probably also because of that early experience. “The spectacle,” says Debord, “is the other side of money,” and holy hell, is that true in this case.

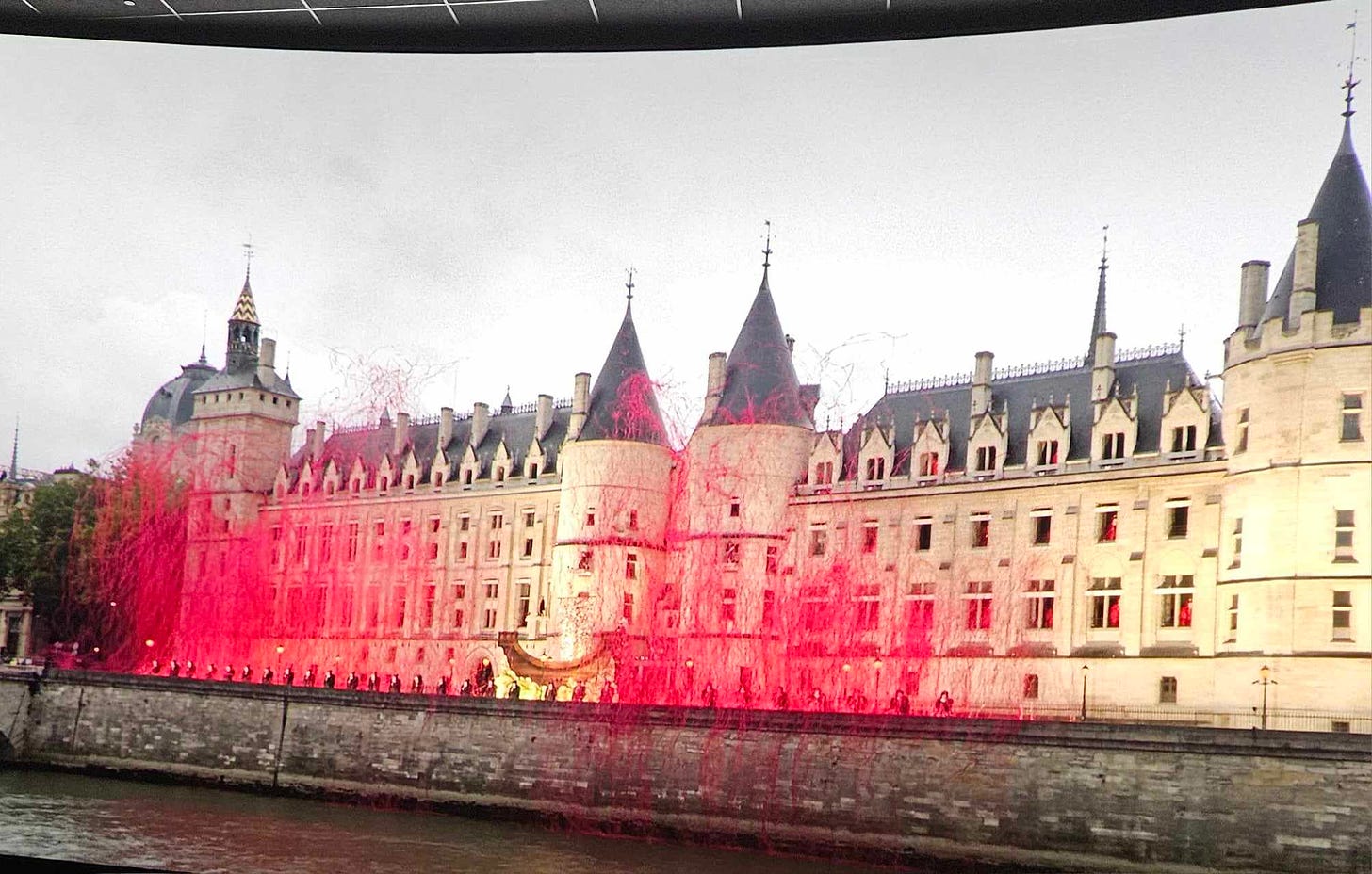

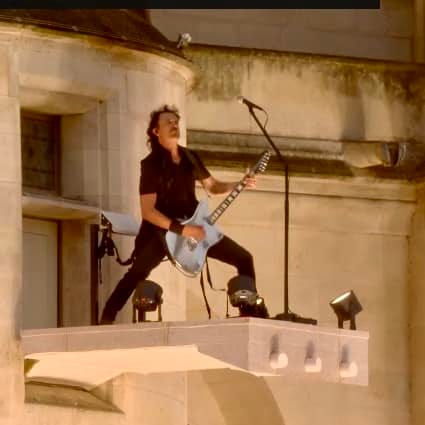

So kill me, I loved it. But on the other hand: what’s not to like, people? The especially gay dance of the Luis Vuitton luggage? The a menage a trois of clowns in a library meant to illustrate the French nation’s special relationship with amour? Or, my favorite moment of all, a powerful vision of the entire French Revolution, when the heavy metal band Gojira played the 18th century revolutionary anthem “Ah! Ça ira” atop the Conciergerie, which displayed numerous people dressed like headless Marie Antoinettes in all the windows – complete with blood gushing out of their necks? At the peak of the performance, there was an explosion of red confetti which made it look like blood was streaming across the building. It was shockingly pretty and not even historically inaccurate

Almost as enjoyable was French-Malian singer Aya Nakamura singing her song “Pookie” and grabbing her vagina whilst accompanied by a frowny-faced old cadre of the Republican Guard Marching Band, the silver mechanical ghost horse galloping atop the Seine for three miles, and last but not least, in honor of France’s role in the invention of hydrogen-powered flight, the cauldron being lit below an enormous golden balloon, which then lifted off to float above the city.

Meanwhile, at the same time all this was happening, either on TV or wherever, the parade of nations was occurring along the Seine itself: 87 boats carrying 206 contingents of athletes, all dressed in their national uniforms and madly waving their flags and genuinely smiling fit to burst. Smiling! Good God, I had forgotten that people could do that on television, but I’ve been seeing a lot of it this week. I like to think those were zeitgeist smiles, and perhaps they were.

I also enjoyed when the parade cut away to French Polynesia, where they are holding the surfing events, and all the contestants in that event also smiled and waved to us from the beach there. Like I said: so much for the time/space continuum. Me, in Sunnyvale, watching something occurring in France and Tahiti, that seems to be splitting the difference between a live parade, pre-recorded hokum, and many other events occurring along the route.

-----

These opening ceremonies were also the first to occur entirely outside a stadium, the concept being that Paris itself was the stadium. In Elias Canetti’s Nobel Prize winning work “Crowds and Power,” the book I based my Ph.D. dissertation on, he discusses the concept of the closed crowd and the open one. The closed crowd – like one in a stadium – is one that’s turned its back on the world. “The closed crowd renounces growth and puts the stress on permanence,” he wrote. “The first thing to be noticed about it is that it has a boundary. It establishes itself by accepting its limitation. It creates a space for itself which it will fill.”

By contrast, he continues, “The natural crowd is the open crowd; there are no limits whatever to its growth; it does not recognize houses, doors or locks and those who shut themselves in are suspect. ‘Open’ is to be understood here in the fullest sense of the word; it means open everywhere and in any direction.”

One way to understand Canetti’s words is that the closed crowd is conservative; the open crowd is its opposite. Another way of thinking about it is that a closed crowd is ticketed, and tickets are by nature hierarchical and capitalistic, while the open crowd is more chaotic, but also more democratic.

Anyway, these are just some thoughts I had while I watched the 4 hour spectacle go by. Another grad school book I thought of was “Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History,” by Dayan and Katz, a text which helped shape how I thought about live performances. The book suggests that there are certain types of live media events – coronations, contests and conquests – that have to be viewed live, and simultaneously, and which therefore have a particular effect on viewers. They call this kind of event “festive viewing,” and posit that these events serve to remind societies to renew their commitments to established values, offices, and persons…or else to change them. They are high holy days, of a sort, that help a dispersed population – who watch alone in their own living rooms – to unify around intentional displays of new ways that society wants you to think. In short:

Media events are rituals of coming and going. The principals make ritual entries into a sacred space, and if fortune smiles on them they make ritual returns. The elementary process underlying these dramatic forms is the rite de passage, consisting of a ritual of separation, of entry into a liminal period of trials and teachings, and of return to normal society, often in a newly assumed role.

The IMAX movie theater in Sunnyvale during the live broadcast was definitely a liminal space, and if Dayan and Katz are right, I – and all of us who watched it – am now returning to ‘normal’ society, only somewhat changed. But how? I mean, all the Frenchy-french stuff was fun and entertaining – the Can-Can, the Lumiere Brothers, Celine Dion singing “Edith Piaf,” that gorgeous golden hot air balloon linking the past and the present…but the Opening Ceremonies, like the Olympics, had a more important message for us, and not, I think, just, ‘We can live as one.’ In the end, it showcased the way that we are now living in a cyborgian spaces, part natural (as shown by the unplanned rainstorm), but partly technological, all mediated by internet-powered wizardry. Just as the mechanical horse that flew along the river Seine turned into a real white horse when it entered the Trocadero, our world is now what Neil Postman called a technopoly, i.e. a society that no longer merely uses technology as a support system but instead is shaped by it—"with radical consequences for the meanings of politics, art, education, intelligence, and truth.”

We can laugh all we want at the Olympic Opening Ceremonies, but I think it is a place where technological change is always on display. A long time ago, my dad was friends with a Hungarian engineer who had won a gold medal in water polo at the 1936 Olympics, and he told me that the thing he remembered best about those Games was not shaking Hitler’s hand, but that there was a tiny black and white television in the Olympic Village, the first any of them had ever seen. On it, they could watch the races as they happened elsewhere in the city, and that ability absolutely flabbergasted the athletes, it was such a brave new world.

To be honest, I felt a little like that looking at the light display emanating from the Eiffel Tower: like I had stepped into the future…and that it might not be all that bad. It’ll be fine, to coin a phrase. Or rather, Ah, ça ira, ça ira

.

Thanks for your observations. I still watch the Olympics every four years, but as an older person, I feel that sports like golf and basketball already receive enough media attention. These sports have other competitions of greater importance. I like the traditional competitions I grew up watching 40-50 years ago — track and field, swimming and diving, and gymnastics. I especially enjoy the running races. Every four years, these races really matter. But the modern games have gotten too complicated for me.

I feel this, the Olympic exception, where cynicism withers in the glare of brilliant style-adjacent athletic costuming and genuine stoke by athletes from everywhere