The 70s were the peak years of my childhood, and the jauntier music of the Beach Boys encapsulates that. Swim team, summer, songs you can sing along to, blue skies and orange beach towels and freckled faces and the smell of coconut oil…Jello powder residue all over the palms of our hands where we licked ourselves into a sugar coma, flip flop tan lines along the tops of our feet. Sitting on the curb at 6 AM waiting for Mrs. Dunn to pick us up for swim practice, wearing our pajamas over our speedos. Tee-peeing team-mate’s houses in the middle of the night. Pancake hut celebratory breakfasts. Ice cream cones at Thrifty, fifty cents for two scoops. My mom complaining that Mrs. Field’s was ripping us off by selling us one cookie at a time, yelling at me for riding without a bike light and not putting my wet towels in the dryer. It seems beautiful in retrospect, but I was very bored during it; I lay on my bed dreaming of the Lower East Side and shitty parts of London, of bands in torn trousers singing White Riot and I Want To Be Your Dog. Alas! No one was going to take me to see the Ramones, but when I was 13, the college guy who rented a room in our house took me to see the Beach Boys and the experience somehow changed my life.

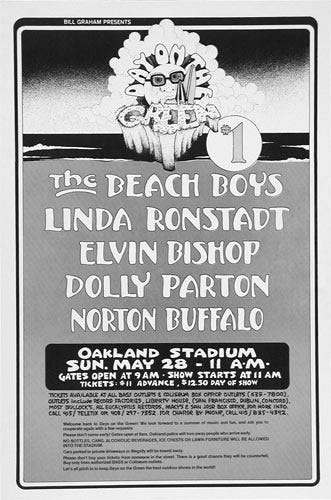

When I was in high school, my parents rented a room in their house to a member of the Stanford tennis team, and she had an older brother on the world tennis circuit, who used to come stay with us whenever he didn’t have a match. One time when he was staying with us, he took me to the Oakland Coliseum to see a Day on the Green, with America, John Sebastian, Elvin Bishop and the Beach Boys. At that time in my life, I was on a swim team, and to say the Beach Boys was our jam was putting it mildly: we blasted them constantly as we drove to meets all over California, and the sound of them said SUMMER. Not only were they easily the band that I knew the most songs of, but they were certainly the only band in the center of a Venn Diagram of what my friends listened to and what I did.

The song I remember best that the Beach Boys sang that day is “Be True to Your School.’ “Be true to your school/just like you would to your girl…” No lyric could express less how I felt about the world at that time. I had absolutely no loyalty to my High School and I hated all the people there who did. And yet, when the Beach Boys sang that song that day, I remember bawling along with them at the top of my lungs, even feeling a swell of pride – and then, understanding even as my heart swole, Grinch-like, how extremely fraudulent a feeling it was. That the Beach Boys could make me do that and feel that was a form of magic. And I knew that it was linked in some way to the setting: the Stadium, the sunset, the screaming girls sitting on the shoulders of their boyfriends singing along at the top of their lungs…I was profoundly moved, not just by the music, which I knew every word of, but by the whole experience. I remember watching toilet paper trails, whole rolls let loose by people in the third tier, float across the sky, and thinking they were so beautiful, twisting and turning in the wind. Thirty years later, I wrote my PhD dissertation on the profundity of seeing music in settings like this, in the company of others, so I think that pretty much says it all.

In 1991, I wrote a review of their show at the Concord Pavilion for the East Bay Express. Here’s a portion of what I wrote.

For me, seeing the Beach Boys was as sad as watching Brian’s Song or reading the Ginger chapters in Black Beauty again – it was one long lump in my throat. At nine o clock sharp, what’s left of the band trooped on stage: Carl Wilson, Mike Love, Al Jardine and Bruce Johnston, that is, plus a host of human overdubs, i.e. an eleven piece band, including three guitars, three keyboards, two percussionists, a saxophone, a bass and six bathing beauties who did various cheerleading routines at the front of the stage in various states of undress.

Normally, one would hold a band accountable for such a hoary old sexist sight, but with the Beach Boys, almost any visual addition to the show is preferable to looking at their physical selves. It’s not just the members’ oldness or ugliness or apparent lasciviousness, but the shadowy evocation of their former joyous innocent selves that’s so incredibly fearful to behold. Leader Love, in particular, is a truly scary man. Dressed in a canary yellow Hawaiian shirt, he reminded me of nothing so much as Bob on Twin Peaks. Every word out of his mouth was mean, from dissing Dudley Dooright lookalike Johnston (who replaced Glen Campbell, who replaced Brian Wilson when he went mad in 1972). Love dissed him, rudely, for writing Barry Manilow’s “I Write the Songs” – and then went on to insult his sax player via his (the saxophonists’) former boss Billy Joel.

Love also got slights in at David Bowie, Mick Jagger and George Bush, and introduced one portion of the show with the following words: “How many of you would like to – despite the fact that they’re outdated, outmoded, stupid and passe – STILL want to hear our car songs?” The man is so filled with venom and hatred it poured out of him in waves. It was kind of interesting, but you had to wonder where it was all coming from, when the formerly avowed Republican had the ..the…disloyalty to dedicate “Be True To Your School” to George Bush: “Our education president,” he sneered. I have probably never seen a heavier moment in rock’ n’ roll than the Beach Boys subsequent rendition of that song. A pall of evil shrouded it – intentionally, I might add, with some queer minor chord added to the chorus and Love prancing and dancing around, full on ironically, to the words ‘Be true to your school/just like you would to your girl” while ogling the six cheerleaders who stood in front of the band doing lively, unironic routines, grinning and pulsating away. Love reminds me of a character in a book by Rebecca West called “The Fountain Overflows,” – an evil man who plays the flute so wonderfully yet torments his family, and when they ask him how he can do both things, he says, “What’s the good of music when there’s all this cancer in the world?” When the Beach Boys, led by the unspeakable Mr. Love, sang “God Only Knows,” I thought of that passage, and its rejoinder, which is, “What’s the harm in cancer when there’s music in the world?”

Because at some point in this concert, one has to come to terms with the fact that the Beach Boys history is so full of good and evil. Certainly, it’s sad that their father was, by all accounts, a psychotic slave driver; that their leader, songwriting genius Brian Wilson, is a sad wreck of a human; that another brother, Dennis Wilson, drown in 1983. But those things are only marginally important compared to their music’s place in the hearts and minds of America, a place that cannot be eradicated by any amount of bad mouthing by Love or anyone else. He doesn’t have to try and whip the audience into a frenzy: their music does it for him. When you hear it – the opening chords of “California Girls,” the bridge in “Do It Again” (“makes your nighttime warm and outtasight”) and countless other moments, you have no trouble understanding what’s made this band so appealing. It endures.

Formed in 1961, the Beach Boys have had close to forty top ten hits. But more importantly, their signature sound is closely tied to the psyche of an entire country. Rock’ n’ roll is supposed to be about oppression and sex, but the Beach Boys music is about so much more: the hopes and dreams and aspirations of a generation, rendered in the smallest, tiniest, detail, without irony, without cliché, without any of the protecting layers of image or humor or brains, in songs that exude innocence and purity despite the surrounding impurity of the world.

Surely those dreams should seem so incredibly little when seen in song form. And yet, underneath the surface of the dumb, dreamy fantasy scenarios – the girl in the T-bird, the boy in the soda shop, and beyond them the beauteous beach – the Bay Boys music is so patently about pain. And pain is pain, whether it occurs in the suburbs or the city, in the 50s or the 90s, to children or to adults. All pain is equal to those who are suffering from loneliness and lack of popularity, the Beach Boys stock in trade. That’s why they’ll never, ever date.

There’s more, but forget it: I wrote that 30 years ago, and I was, I believe prescient. You will probably be able to see some version of the Beach Boys this summer (or maybe next) at a local winery or Native American Bingo Parlor, and it will be more or less the same experience. And you know what? I would, if I were you.

Every word of this is true